2015 Special Recognition: Cross-Lab Redundancy in Forensic Science

In 2012, Massachusetts state chemist Annie Dookhan of the Hinton State Laboratory was arrested and charged with obstruction of justice, perjury, and tampering with forensic evidence in connection to over 35,000 criminal cases. This unprecedented crisis in the state criminal justice system put into question the validity of thousands of convictions. Consequently, the appeals process for these convictions continues to play out in the courts today, exonerating wrongly convicted citizens and costing the state millions of dollars in time and resources.

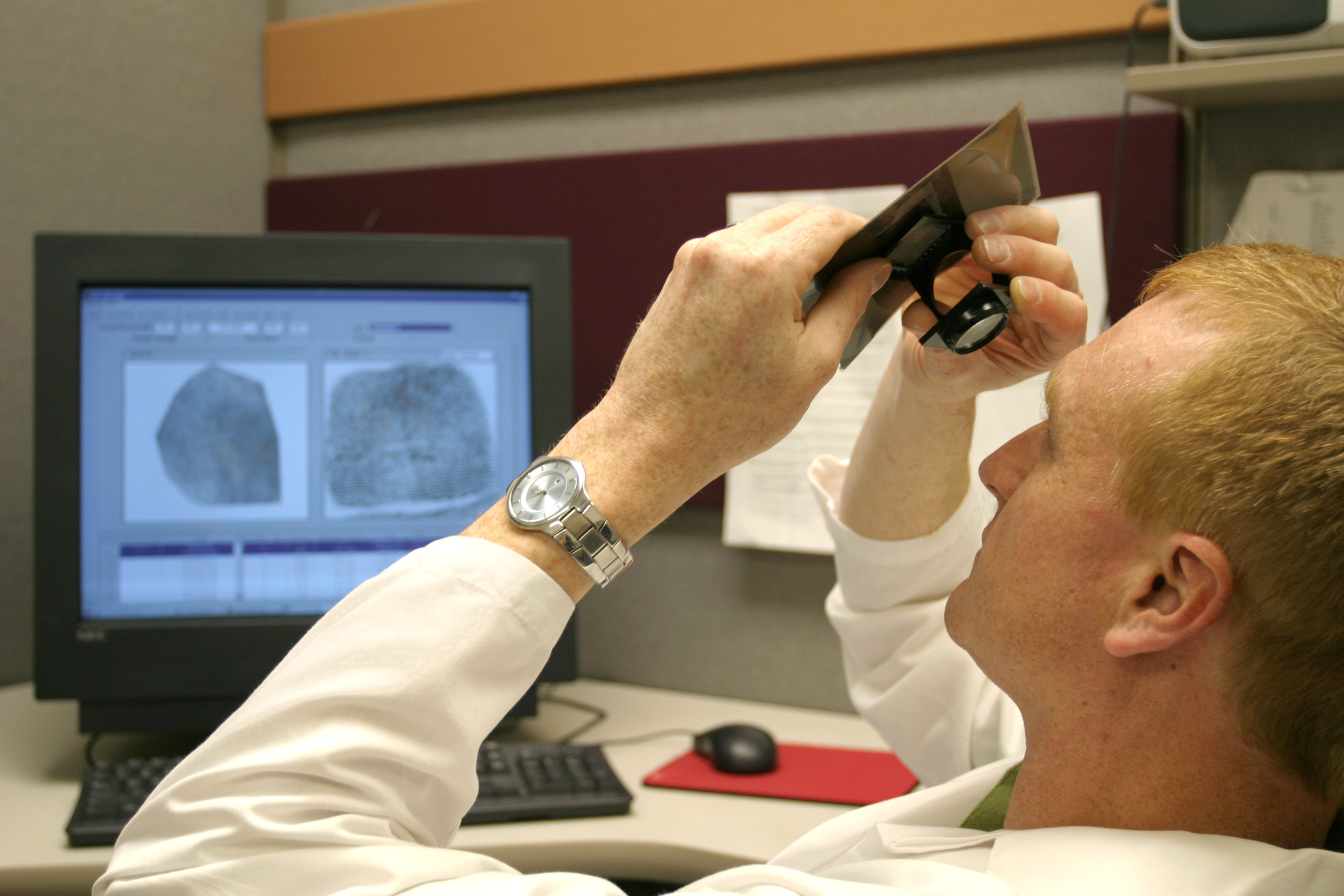

The Dookhan scandal exposed structural weaknesses in Massachusetts crime labs. Currently, case evidence is taken in and examined by one lab, with the same lab providing the solitary interpretation of test results to juries, police investigators, and prosecutors. No other experts are called in to offer analysis, or to check that no processing errors were made. This two-fold monopoly makes it difficult to detect when a crime lab has made an error, whether accidental or malicious.

It is in the state’s best interest to introduce a method of checks and balances in the criminal justice system. Roger Koppl, a professor of finance at Syracuse University and senior fellow for the National Center for Policy Analysis, has written a number of articles on how to improve forensic science. Koppl proposes that Massachusetts adopt a system of cross-lab redundancy. Cross-lab redundancy is the requirement that a random percentage of case evidence be tested and analyzed by multiple crime labs, instead of one lab processing all evidence. Because only a fraction of cases would be subject to multiple analyses, forensic examiners would never know when they were working on a case that was being analyzed by other labs. The three labs would independently examine, interpret, and submit the evidence. Juries, police, and prosecutors would receive the findings from all three labs, and then judge the evidence conclusive or contradictory. Koppl writes that this also eliminates the problem of crime labs being biased towards the prosecution, and allows the defense to have access to evidence analysis.

Because it is an organizational change, no legislation is needed to enact the policy. Replacing “monopoly forensic science” with “networked forensic science” would establish a more transparent process and improve the effectiveness of the criminal justice system. False convictions are enormously costly: they result in the incarceration of innocent citizens and jeopardize public safety. Error reduction in forensic evidence would allow for more justice and greater public safety in Massachusetts.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!